Inside Damascus's Reconstruction Lab: Navigating the Framework of Return and Recovery

Ten Takeaways

- In the aftermath of the regime’s consolidation of control over Damascus in 2018, no comprehensive framework for the return of displaced people and rehabilitation of conflict-affected areas has been applied. Instead, decisions have been made locally by various governing entities and security organizations. This localization strategy has left returnees subject to extortion by local security personnel, criminal gangs, and contractors.

- Contrary to the official discourse encouraging return and prioritizing early recovery, the regime’s actual policy demonstrates the opposite. Current regulations and decisions remain restrictive, influenced by political, security, and economic considerations that serve the regime’s interests, particularly in unplanned informal areas and those designated for urban development.

- Just as the Syrian regime effectively employed depopulation and demolition tactics during the conflict to win its war against rebellious communities, it continues to utilize similar tactics to shape the post-conflict period. These measures go beyond collective punishment to include strategic economic and political objectives.

- The regime views any current return and rehabilitation process as a temporary phase, pending the accumulation of sufficient financial and political resources for the execution of its pre-conflict urban development projects. These projects will involve the total demolition of affected areas, which are to be supplanted by high-end residential and commercial complexes, drastically altering the local socio-economic and urban fabric.

- For this indefinite interim period, the regime has allocated fewer resources to the recovery of damaged areas, with efforts focused on rehabilitating security and government buildings, serving wealthier neighborhoods, and initiating tourist and commercial projects. Consequently, returnees bear the financial burden of debris removal, property rehabilitation, and restoration of basic services. Properties owned by those who lack the capacity to initiate repairs are either looted, confiscated, or purchased by regime-linked businessmen at undervalued prices.

- The regime is keeping captured neighborhoods depopulated not only because of legitimate financial constraints and security considerations but also as a strategic choice to provide fewer services and recovery assistance to discourage return to these areas. A low or non-existent rate of return will result in less resistance to the eventual implementation of regulatory and development plans, while minimizing the amount of financial compensation authorities would have to pay to occupants of properties affected by these plans.

- The majority of current returnees come from within regime-controlled areas and are therefore more likely to obtain security permits. The return of refugees from other countries and internally displaced persons (IDPs) from other controlled areas remains highly restricted and/or significantly risky. Economic factors, particularly the desire of the displaced to avoid paying rents in their temporary locations while they own properties in their hometowns, appear to be the key drivers of such internal return. While these individuals face lower risks compared to refugees abroad or IDPs in other areas of control, they still encounter significant challenges: inadequate security, the continuous threat of looting gangs, a lack of basic services, financial constraints for property rehabilitation, and limited access to legal support. These difficulties have driven some to leave their neighborhoods again after returning.

- Considering the regime's reconstruction blueprint, a large-scale, regime-led rebuilding effort might cause more harm than good. Alternatively, facilitating and encouraging low-risk return of IDPs from within regime-controlled areas coupled with meaningful restoration of returnees' properties could pose a substantial challenge to these plans. This approach could involve the distribution of small and micro-grants directly to returning IDPs to enable property rehabilitation and the restoration of local economic activities. Ultimately, re-establishing pre-conflict community structures seems the only viable strategy to safeguard these neighborhoods from their ultimate dissolution.

- The materialization of a strategy to facilitate return requires leveraging financial, political, and legal tools. This should include providing support for civil society and grassroots initiatives and legal consultation for returnees. Additionally, donors must associate political pressure and operational conditions with the implementation of early recovery projects within regime-held areas. These conditions must encompass guarantees to issue return and rehabilitation permits for potential returnees and improve overall security in returning areas.

- An examination of case studies such as Yarmouk Camp and Daraya reveals that grassroots initiatives, backed by local figures exerting legal and political pressure on the Syrian regime, constitute the most effective method to enhance return and demand improved services. Despite the regime's firm security grip, hostile legal framework, and chaotic operational environment, reversing its plans is still possible.

Introduction

In October 2022, Syrian Prime Minister Hussain Arnous inaugurated the commencement of two commercial tourist projects in Damascus1: Nirvana Complex, a luxury commercial and tourist development in the Hijaz area (at the site of a cherished historic building that was demolished2), and Victoria Hotel, a five-star accommodation in central Damascus. These projects are in close proximity to Basilia and Marota, high-end urban development complexes constructed on lands forcibly depopulated during the conflict.3 The announcement of luxury housing schemes in a country devastated by conflict and within a city suffering from massive destruction and housing shortages encapsulates the contradictions of the regime’s policy for reconstruction and early recovery not only in Damascus but in the whole country. This policy can be summarized as minimizing return and rehabilitation activities in areas where the regime plans to implement its pre-conflict urban development plans while concentrating its resources in “economically profitable” sectors and locations. This research paper aims to unravel this policy, delving into its legal, political, and security foundations, drawing key lessons about the post-conflict landscape in Damascus.

Damascus was selected as a primary case study due to the city's extensive destruction and the scale and diversity of projects implemented in recent years. Since the outbreak of the conflict in 2011, the city has experienced numerous rounds of displacement, destruction, return, and reconstruction. Our objective is to engage with the various facets of post-conflict policies instituted by the regime since its recapture of Damascus in 2018. Given the political, security, and economic significance of the city, an in-depth analysis of Damascus will provide insights into what reconstruction under Syria’s current political circumstances might look like.

The paper is structured into four sections. The first section provides a historical overview of the roots of the urban crisis in Damascus, followed by an examination of the patterns of destruction and displacement during the conflict. The subsequent section delves into the legal, political, and security frameworks governing several aspects of early recovery and reconstruction efforts, such as return, debris removal, housing rehabilitation, and regulatory plans. The projects related to early recovery that have been implemented by the Damascus Governorate Council (DGC) will be quantitatively analyzed in the third section to scrutinize the council’s geographic and sectoral priorities. The final section will investigate two case studies, namely southern Damascus and the Qabun area, to assess the current applications of return and rehabilitation.

The researchers conducted 10 interviews with current residents or displaced persons from Damascus between May and December 2023. Data on early recovery projects were gathered from the Facebook pages of Damascus and Rural Damascus governorate councils and triangulated with secondary data from local Facebook pages that provide regular updates on the situation on the ground.

Historical Roots of Urban Crisis in Damascus

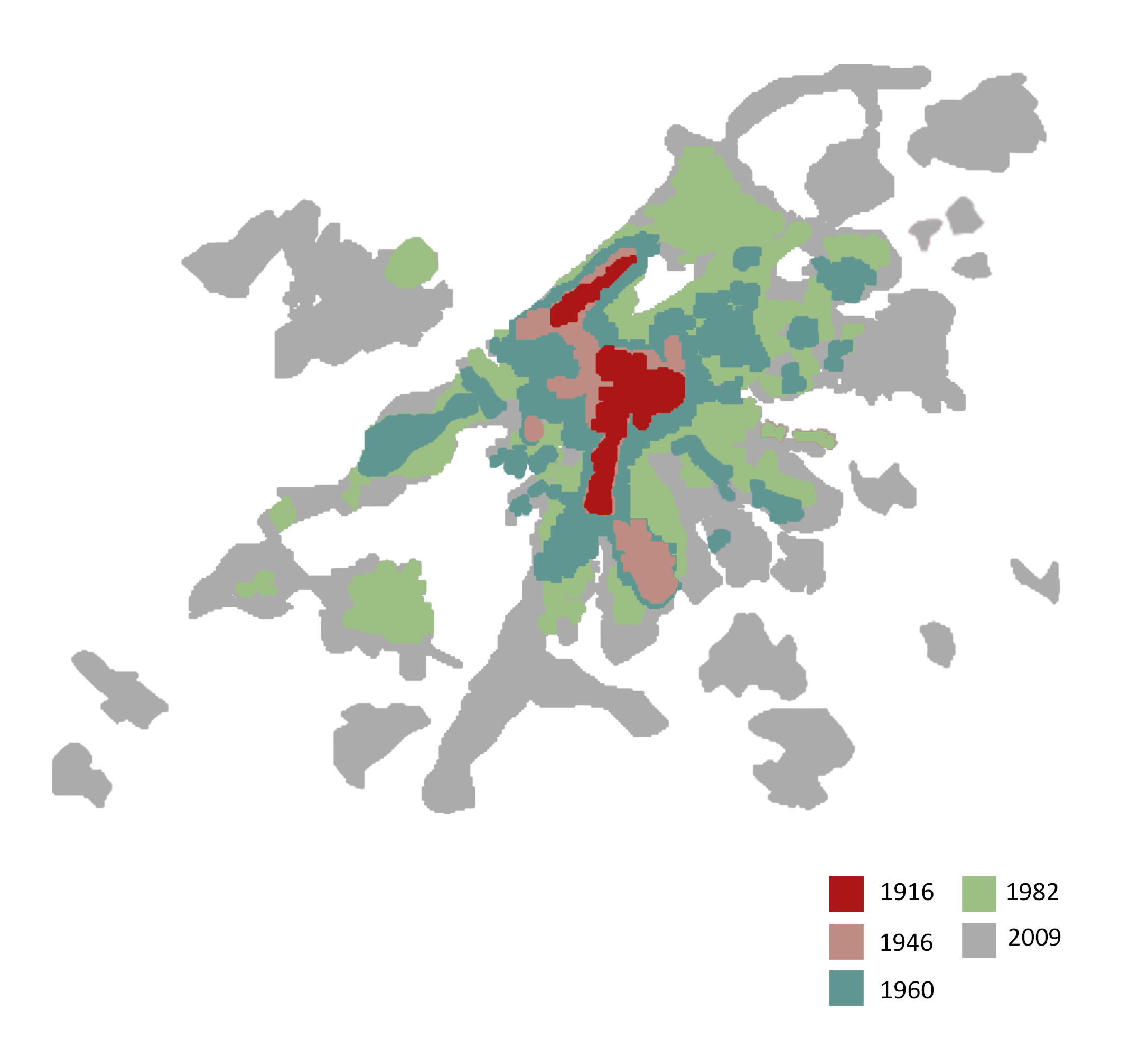

The paradox of Damascus, designated by the United Nations as the Arab cultural capital4 in 2008 yet consistently ranked as the worst city in the world to live in for 10 consecutive years from 2013 to 2024, encapsulates much of the city’s complex and contradictory tale.5 The degradation of living conditions in what is believed to be the oldest continually inhabited city in the world traces its roots back several decades before the outbreak of the conflict in 2011, and is marked by a pattern of urban development that has fostered socio-economic disparities and a stark dichotomy between well-regulated high-class neighborhoods and impoverished informal settlements.6 Since the 1970s, such segregation has been aggravated and politicized by several planning policies and regulations applied by the Syrian regime.

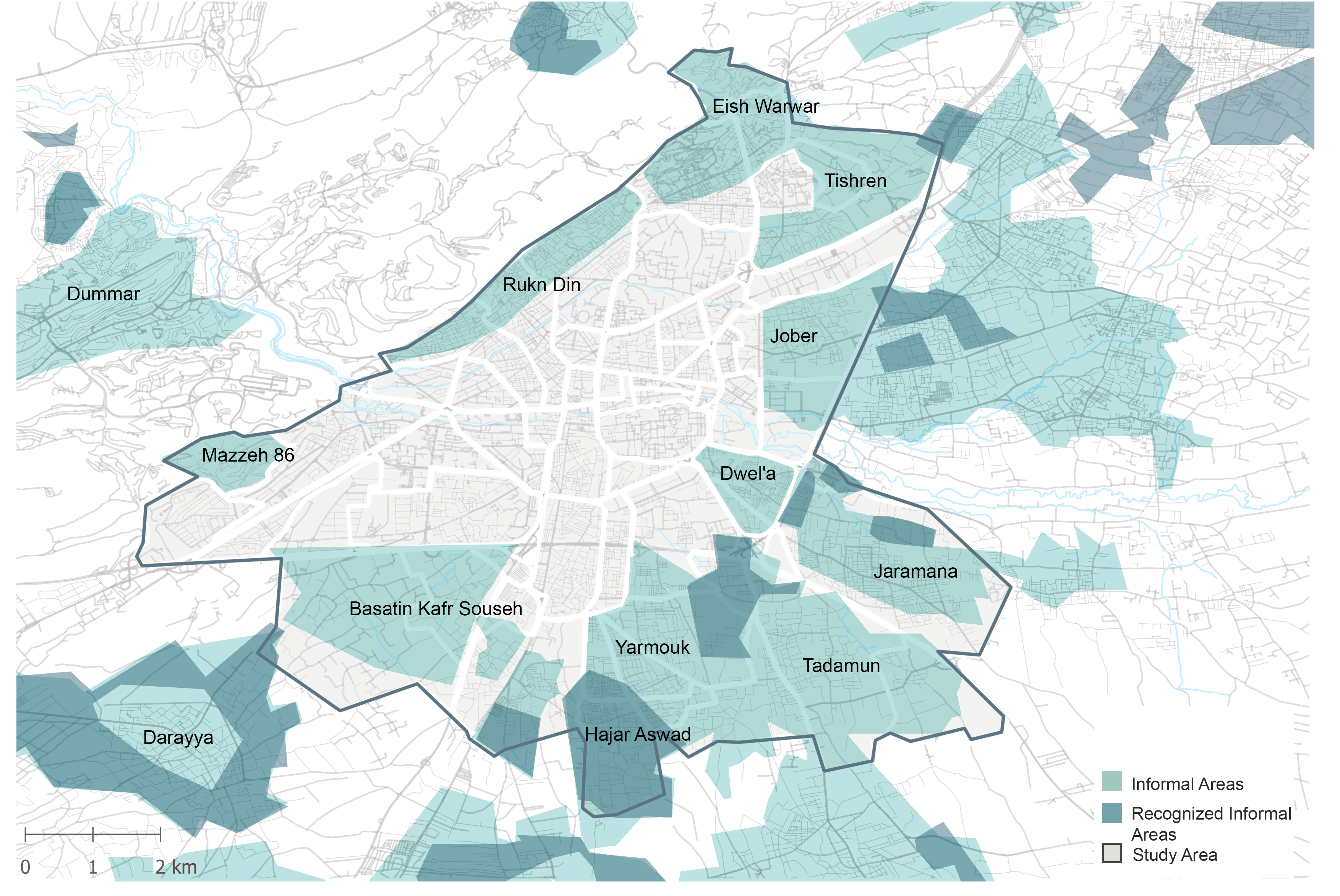

Damascus is not only economically segregated but is also ethnically and religiously fragmented. Christians have had an enduring presence in the old city for centuries, coexisting with the Sunni majority. Alawites, who migrated from coastal areas to work in the public sector and the army, are concentrated in the informal neighborhoods of Mezzeh 86 and Eish al-Werwer. Similarly, the Druze population is mainly situated in Jaramana.7 For decades, the Kurdish community resided on the slope of Qasyoun Mountain in Rukn al-Din, later joined by new Kurdish migrants who fled the Jazira region during periods of drought in the 1980s. Finally, Palestinian and Iraqi refugees found shelter in Yarmouk in 1948 and Jaramana in 2003, respectively. Due to limited residential mobility,8 coupled with public employment and housing policies, these segregation lines have shaped the socio-spatial characteristics of Damascus for decades.

Like many other major cities, Damascus’s urban landscape is far from homogeneous. The spatial inequality is so evident that it can be easily observed with the naked eye from an aerial view. The most significant division lies between formal and informal areas. The peripheries of Damascus, particularly along the southern and eastern edges, have seen a proliferation of informal settlements. This has been a direct consequence of the government’s failure to provide adequate housing to accommodate population growth and the influx of newcomers and rural migrants. This predicament has been further exacerbated by liberalization policies that privatized the housing market, leading to a surge in real estate prices. These policies have prioritized profitable luxury urban development projects over affordable housing.9 Even when affordable housing was built, it was primarily allocated to public employees and army soldiers,10 often driven by political and sectarian considerations. This approach has further deepened the divide in the urban landscape of Damascus.

While the official policy toward informal areas, as manifested in early laws issued in the 1960s and 1970s, stipulates the demolition of all buildings in violation of existing codes, including informal housing units, in practice, the regime has tended to balance between three approaches: rehabilitation (improving existing structures), penalization, and renewal (demolishing and reconstruction).11 Beginning in the 1980s, the state initiated the provision of basic services to these haphazard areas, while retaining the authority to demolish properties whenever it deemed necessary. Additionally, while offering narrow legal windows for some owners of illegal housing to regularize lands division (Law 33 of 2008) or obtain a building license for existing informal buildings (Law 46 of 2004),12 the regime encouraged private real estate developers to construct social dwellings and/or renovate the informal areas on public lands (Law 15 of 2008).13

It can be argued that the regime’s ultimate goal has always been the demolition of all informal areas and integration with the government’s regulatory and development plans. This vision was unachievable prior to the conflict due to a lack of financial resources and the coercive power needed to evict, relocate, and compensate hundreds of thousands of residents in these areas. Nevertheless, the outbreak of the conflict presented a unique opportunity for the Syrian regime to realize its plans, given the widespread displacement and destruction that ensued. The strong correlation between urban informality, destruction, and displacement is not merely coincidental; it is a pattern observed in other major cities such as Aleppo,14 Homs, and Hama.15 If one conclusion can be drawn from this, it is that the destruction was not solely a necessity to secure military victory, but also a politico-economic endeavor. This study argues that the regime-led reconstruction is unlikely to be less destructive and hostile for the urban environment and society than the war.

Damascus During the Conflict

The Syrian uprising commenced with the first protest erupting in Damascus’s Souk al-Hamidiyeh on March 15, 2011, followed by another near the Umawi Mosque three days later. As the demonstrations spread throughout the country, activists in Damascus managed to organize thousands of revolutionary activities. Over time, these activities became concentrated in specific neighborhoods, including Midan, Barzeh, Qabun, Qadam, Rukn al-Din, Kafr Souseh, and Jober. Learning from Tunisia and Egypt, the Syrian regime exhibited less tolerance for protests in the capital, prioritizing the prevention of protestors from reaching central areas like Abbassiyyin Square. To achieve this, the regime implemented a strategy of dividing the city into security sectors, separated by numerous checkpoints. The capacity of different neighborhoods to solidify mobilization was affected by the aforementioned socio-economic and sectarian lines of segregation. Mobilization primarily persisted in informal, densely populated, and socially homogeneous neighborhoods.

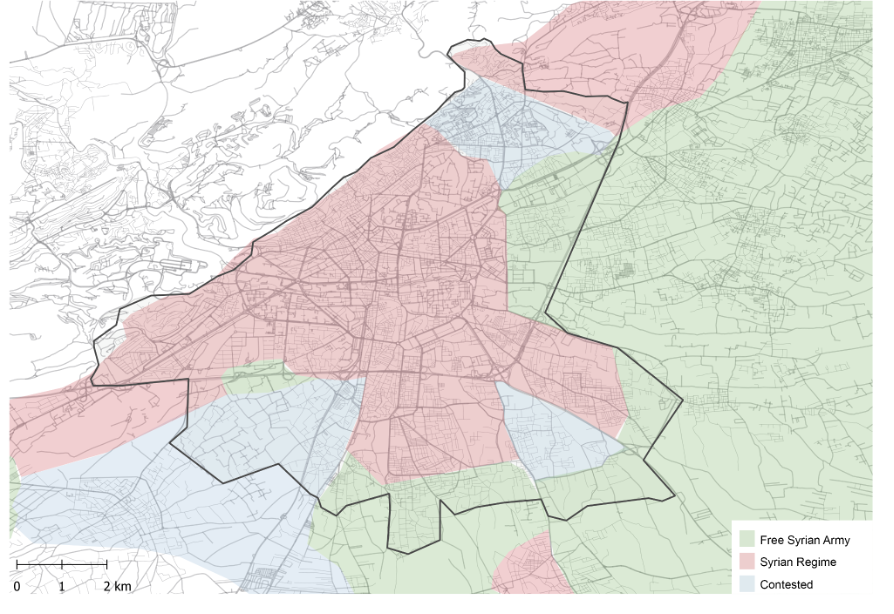

To safeguard protesters and repel security incursions, local cells of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) emerged in most rebellious neighborhoods. The FSA’s operations gradually concentrated in southern Damascus (al-Hajar al-Aswad, Tadamun, Qadam), the eastern periphery (Qabun, Barzeh), and areas adjacent to western Rural Damascus (Kafr Souseh, Madamiyet Elsham). Nevertheless, the Syrian regime swiftly regained control over some areas like Midan, Kafr Souseh, and Mezzeh. By July 2012, the initial military control line was established, primarily confining the FSA to the southern and eastern outskirts. However, in 2014, jihadist groups such as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Jabhat al-Nusra took control of parts of southern Damascus, including Yarmouk Camp, al-Hajar al-Aswad, and Qadam, adding additional complexity to the map of military control.16

Despite their retreat to the city's fringes, the geographical connection with Rural Damascus enabled the FSA groups to hold their ground and gradually encroach upon regime-held positions. In response, between 2013 and 2014, the regime employed different strategies across the city. First, to prevent Qabun from serving as a link between opposition forces in Damascus and Eastern Ghouta,18 the regime depopulated and razed significant portions of the neighborhood. Second, harsh sieges were imposed on neighborhoods in southern Damascus, such as Yarmouk, al-Hajar al-Aswad, and Tadamun. Third, the regime initiated truce or “reconciliation” agreements with other neighborhoods, often facilitated by local intermediaries. Some neighborhoods, such as Barzeh, Tadamun, Qadam, and Yalda, brokered truce agreements with the regime, thereby allowing the regime to concentrate its military efforts on remaining opposition-held areas.

The varying trajectories experienced by former opposition-controlled neighborhoods have played a role in shaping their humanitarian and security conditions throughout the conflict as well as the patterns of displacement and destruction. Besieged neighborhoods in southern Damascus endured dire humanitarian crises and extensive destruction, setting them apart from other areas that entered truce agreements with the regime. Qabun and Jober, initially depopulated, evolved into frontlines between regime and opposition forces. They also functioned as supply routes for food and fuel to the besieged Eastern Ghouta area through an extensive network of underground tunnels.19

Beginning in 2016, the Syrian regime adopted a new strategy, targeting each opposition enclave in Damascus and Rural Damascus individually with intensive bombardment campaigns. Barzeh became the first neighborhood to fall entirely under regime control in May 2017,20 leading to the displacement of those who refused to engage in so-called reconciliation agreements with the regime, many of whom were transferred to northern Syria. By mid-2018, all other opposition-controlled areas in Damascus and Rural Damascus followed suit. Opposition-controlled neighborhoods experienced varying degrees of displacement during the conflict. Some, like Qabun and al-Hajar al-Aswad, were nearly depopulated, while others such as Barzeh, Yalda, and Babella managed to preserve a relatively sizable portion of their local population due to agreements with the Syrian regime.21 The displaced sought refuge in other neighborhoods within Damascus, relocated to different towns or cities within regime-controlled territories, moved to northwest Syria, or fled the country altogether.22

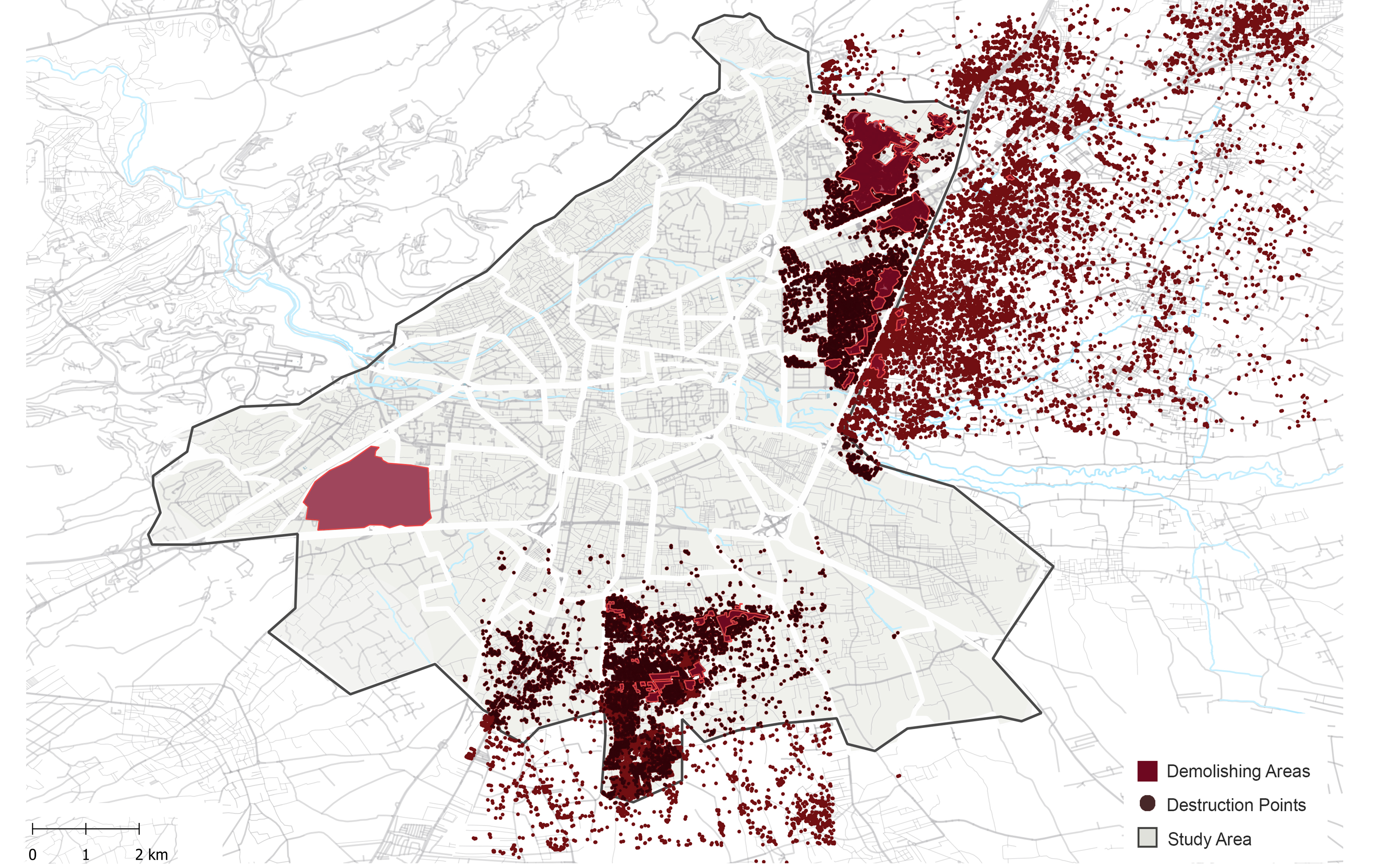

The interplay of war, siege, truce, and displacement has allowed the Syrian regime to gain full control over Damascus. However, even five years after the regime’s return to full control, the city is far from entering a phase of recovery. Very few steps have been taken to address the destruction caused by the war, initiate a genuine process of social reconciliation, or facilitate the return of refugees or IDPs. On the contrary, the destruction and ruination of areas formerly controlled by the opposition have continued. Some areas have been razed to serve as recycling sites for rubble, while others have been converted into open sites for the regime’s military and militia groups to extort locals. By the end of 2023, the number of returnees in Damascus did not exceed 27,300 people.23

Legal and Political Framework of Return and Reconstruction

Following the complete takeover of Damascus in 2018, the Syrian regime implemented a series of laws, regulations, and decisions to exert control over the processes of return and rehabilitation. This section will provide an in-depth analysis of the legal framework governing the current reconstruction efforts and plans in Damascus, with a particular focus on neighborhoods that were formerly under opposition control but were recaptured by the Syrian regime between 2016 and 2018. The discussion will center around four key areas: the return of IDPs and refugees, debris removal, property rehabilitation, and urban regulatory plans, and will shed light on the conditions and regulations that have shaped the post-conflict landscape in Damascus and influenced the decisions of residents regarding return and rehabilitation.

Considering the dynamics of return and rehabilitation, Damascus can be abstractly divided into five categories, excluding neighborhoods that remained under the regime’s control throughout the conflict:

- Areas recaptured by the regime in mid-2013 at the outskirts of southern Damascus such as Hjeireh, Thiyabiyeh, and Sbeineh. The return to these towns has been mainly restricted since recapture, due either to the high level of destruction or to their proximity to strategic locations such as Iranian militia headquarters in Sayyeda Zeinab or Damascus International Airport.

- Neighborhoods that engaged in political truce agreements with the regime in 2014 but were militarily recaptured in May 2018. The return and rehabilitation have been somewhat less restricted there due to the relatively lower level of destruction and displacement. Examples of such neighborhoods are Barzeh, Yalda, Babella, Beit Sahm, and Qadam.

- Neighborhoods that were militarily captured by the regime and suffered higher levels of displacement and destruction, such as Yarmouk, al-Hajar al-Aswad, and Tadamun. Return to these neighborhoods is conditional, based on factors like the level of destruction and security considerations.

- Neighborhoods that were totally destroyed mainly by bombardment during the conflict or later bulldozed by the regime, as in Jober and parts of Qabun and Tishrine. These areas are officially designated for development, and return has been entirely restricted.

- Neighborhoods where urban development has already started as in Marota City and Basilia City. Existing buildings have been razed, and alternative housing options have been promised.

Return

In theory, conflict-affected neighborhoods are categorized into internal sectors (A, B, C, etc.) based on the level of damage as assessed by technical committees assigned by the governorate council. Although the council officially holds the authority to announce return decisions, the security committee is believed to be the final decision maker in this regard. This is substantiated by the fact that affected areas are also divided into security zones, each under the influence of a specific military or security branch, primarily Military Security or the Fourth Division. These entities effectively control movement to and from all affected neighborhoods through their checkpoints.24

Return is permitted individually to each sector based on its level of damage and security status. Return regulations may differ from one neighborhood to another, but there are three common prerequisites for all potential returnees: providing proof of property ownership, demonstrating the structural stability of the building, and obtaining security clearance to enter the area. In effect, the combination of these three requirements poses significant challenges for a large portion of IDPs and refugees who resided in now heavily damaged areas and lack official ownership certificates or have connections — or relatives (up to the fourth degree) with connections — to opposition groups, whether in governance, civil society, or military capacities.

There is no central security body that is responsible for issuing returning permits. Typically, local security headquarters and checkpoints oversee issuance within their areas of influence. However, this decentralized process exposes potential returnees to extortion and demands for bribes and royalties by checkpoint personnel. For instance, return permits to Tadamun have been influenced by the National Defense Forces (NDF), which routinely request bribes from applicants via local mediators. Furthermore, the multiplicity of actors and authorities often results in contradicting decisions. For instance, although returnees in theory only need to apply for security permits through the local council in Yarmouk Camp25 and Daraya,26 their entry could still be denied at local checkpoints. Returning without obtaining a security permit can lead to arrest. For example, in April 2023, 15 people were arrested in Yarmouk Camp for entering without a permit or staying for more than 24 hours for those holding visiting permits.27 Permitted returnees are not allowed to host visitors for more than 24 hours; violators risk imprisonment.

In addition to return permits, people can also apply for short-term property visitation permits, typically valid for just one day. This option is usually pursued by individuals seeking to assess the condition of their properties, especially in areas where full return is not yet permitted. It is also utilized by those who may not wish to return immediately but want to observe the status of public services and the real estate market. Other residents temporarily return to inspect their properties and secure them by installing doors and locks to prevent vandalism and looting.28 Visiting permits are usually issued directly at local checkpoints and are often associated with bribery and extortion.

Notably, in recent years, the Syrian regime has relaxed restrictions in some areas, such as Yarmouk Camp and parts of Qabun, for both political and economic reasons.29 As will be demonstrated in the case studies, the easing of return to Yarmouk Camp can likely be attributed to political pressure exerted by various Palestinian factions.30 In other cases, such as in Qabun and Tadamun, the failure by the regime to obtain adequate investment to implement regulatory plans might explain the loosening of restrictions on return. For instance, after denying return to Tadamun for two years, as the neighborhood was slated for complete demolition and redevelopment, the regime eventually permitted conditional return in September 2020,31 presumably after putting the development plans on hold.

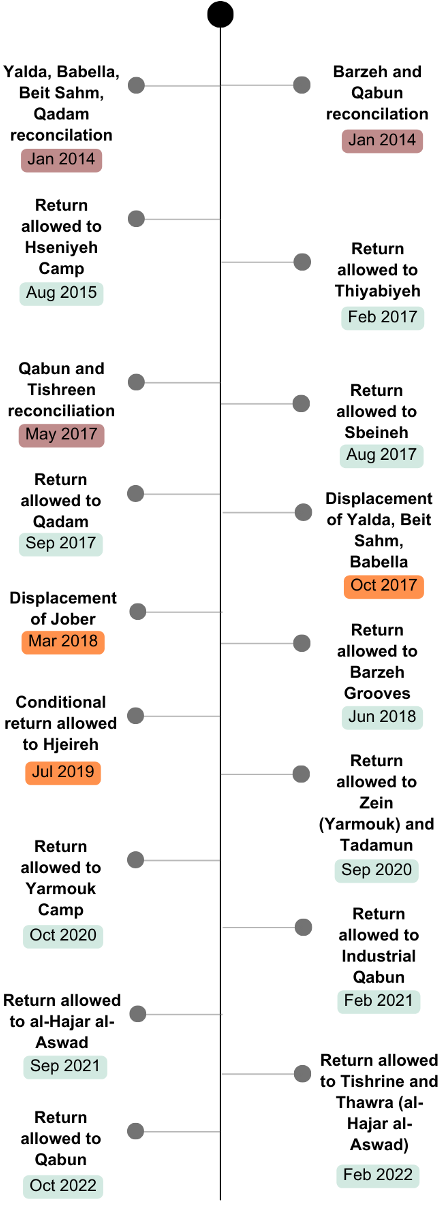

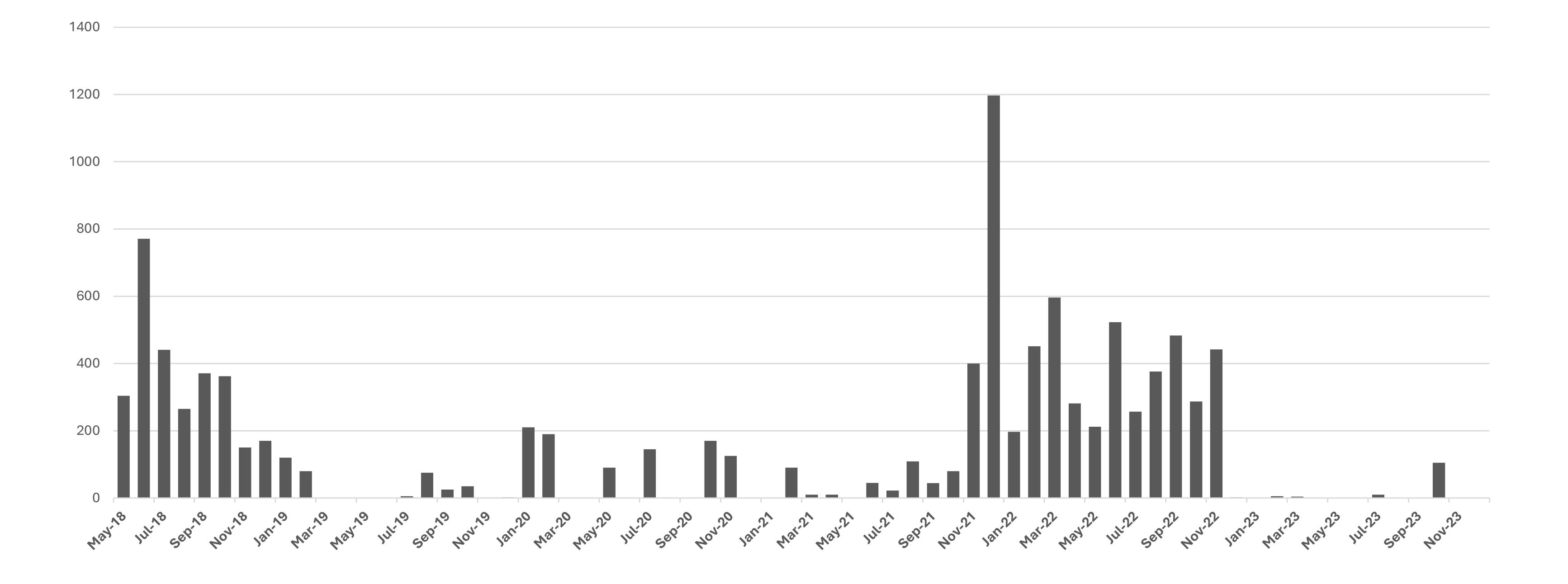

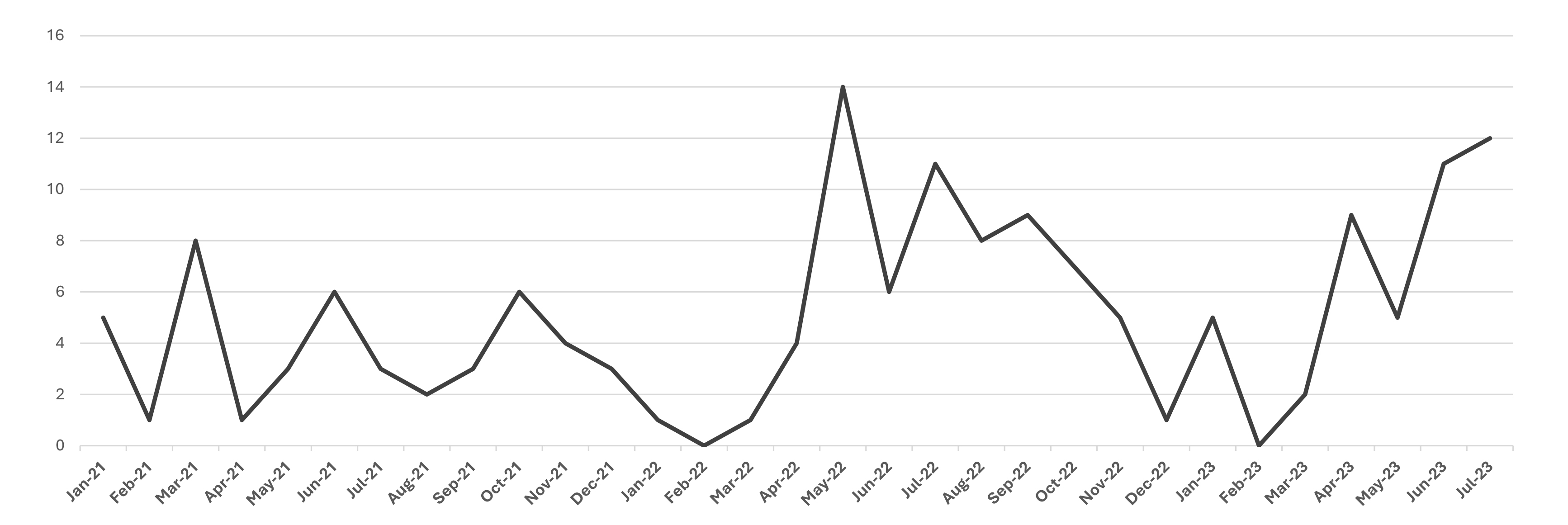

Despite these efforts to encourage return, results have continued to be limited. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA),32 between 2016 and 2023, only 27,303 people returned to Damascus from outside the city, as seen in Figure 2. In fact, the actual number of returnees might be even lower, as many IDPs return temporarily to check on their properties before leaving again. The data shows that return rates were higher between June and September 2018, following the end of military operations in southern Damascus. Return movement also increased during 2022 before completely plummeting in 2023 due to the regime’s failure to restore basic services and facilitate rehabilitation, along with lack of security and financial assistance.

The return to regime-controlled areas from surrounding countries such as Jordan and Lebanon continued to be minimal as of 2023,33 with the majority of returnees to Damascus coming from other regime-controlled areas as they are more likely to obtain security permits. According to a 2024 survey conducted by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), fewer than 2% of Syrian refugees across the Middle East expressed their willingness to return to Syria over the next year and 55% stated they never want to return.34 However, as will be discussed in the following sections, the large-scale destruction in most affected neighborhoods, coupled with the absence of legal frameworks and mechanisms to support property rehabilitation, remains a major obstacle to return even for those residing within regime-controlled areas. To put this claim into perspective, in Qabun, only one quarter of the whole neighborhood was considered suitable for return.35 In Western Harasta, local media sources claimed in 2020 that only 40 houses in the whole town might be suitable for return under current requirements, a town with a pre-war population estimated in 2004 at 68,000.36

Debris Removal

Law 3 of 2018 is the main legal framework governing the removal of rubble from buildings damaged by either natural or unnatural causes, including those considered in violation of building codes and slated for demolition.37 The law stipulates that each administrative unit is responsible for identifying affected areas and establishing technical committees tasked with categorizing damaged buildings, verifying ownership, and assessing the rubble within a 120-day timeframe.38 Subsequently, residents have only 30 days to prove their ownership claims, otherwise, their properties will be subject to demolition by local authorities. It must be noted that the majority of refugees and IDPs are not able to comply with such a short period of time as many face security restrictions or are unable to provide ownership certificates, which might not exist in the first place or were damaged or lost during the conflict.

Despite being issued during the conflict and aimed ostensibly at addressing the destruction experienced in Syrian cities, the law has failed to address key aspects of the problem, such as the urban informality and the massive scale of displacement, and exhibits several shortcomings. To name one, it stipulates that owners have the right only to the rubble’s monetary value, but the local administration is to estimate the value of the rubble after selling it in public auctions or recycling it. In both cases, the demolition cost is deducted from the value of the rubble itself. IDPs with damaged properties often find their rubble removed by the municipality, which typically seizes it under the pretext of covering the demolition expenses.39 It is worth mentioning that only the rubble of partially damaged buildings can be removed by owners, while destroyed properties necessitate a different and special permit for removal.

Furthermore, the actual implementation of the law is no less harmful. People are often left alone to remove the rubble of their damaged buildings without any governmental support. Rubble removal initiatives are primarily led by residents, local initiatives, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). However, funds allocated by international NGOs for the purpose of rubble removal typically target clearing main streets and public facilities.40 For instance, although the Damascus municipal council announced that it would cover the cost of rubble removal in Yarmouk Camp between September and October 2021,41 in reality, local contractors in charge of the business of rubble removal, who are mainly influenced by or affiliated with local militia and security groups, extorted locals by either demanding payment for removing the rubble or seizing valuable materials in exchange for its removal.42

In other cases, although it blatantly contradicts the law, debris removal is often made one of the conditions of obtaining return permits, as observed in Yarmouk Camp, Tadamun, and Qabun. Not only must residents bear the cost of rubble removal, but they also are prevented from receiving the value of the rubble in a multitude of ways. In fact, before any return takes place in a neighborhood, valuable materials such as windows, doors, electrical appliances, and steel and copper pipes and wires are likely to be looted by pro-regime militia groups, leaving the remaining rubble nearly worthless.43 In other scenarios, residents are instructed to move their rubble to the main roads for removal by the municipality,44 where it is often stolen before collection, making it appear as if the municipality aims to make the job easier for looting gangs.

In conclusion, the implementation of the current framework of debris removal does not provide financial assistance to affected residents or safeguarding of their properties from looting or contractors’ extortion, and in important ways, obstructs or prevents effective rehabilitation.

Housing Rehabilitation

Like return, the process of housing rehabilitation in affected neighborhoods is mainly governed by domestic regulations and decisions made by local municipalities and security branches. Individuals seeking to rehabilitate their properties are required to obtain a security clearance and provide personal and family identification, proof of ownership, and a technical inspection report to verify the structural soundness of the property.45 In practice, this means that rehabilitation is not possible in neighborhoods with high levels of damage, informal areas, and for properties belonging to displaced persons or those who were involved in any civilian or governance activities during the opposition control period.

Legally, there are three types of rehabilitation permits: light rehabilitation (involving cladding and tiling work), building rehabilitation (comprising structural rehabilitation), and building reconstruction. Permits for reinforcement and partial reconstruction are typically obtained from the Damascus Governorate Council,46 unless the land is classified as a heritage site (as is the case for 6,000 houses in Old Damascus),47 and additional approvals from the Directorate of Endowment and the Directorate of Antiquities and Museums might be necessary. Obtaining permits becomes substantially more challenging in the case of common ownerships (public and private) as in Souq Srijeh in Old Damascus, where a state-owned construction company has been ineffectively repairing the marketplace and streets, while local officials refuse to issue rehabilitation permits for individual houses.48 Informal communities seem to be the most difficult areas in which to carry out rehabilitation work. According to Law 40 of 2012, only informal properties constructed before the law’s issuance can obtain light rehabilitation permits, meaning that buildings constructed during the conflict cannot undergo rehabilitation, while no structural enforcement for older buildings is allowed whatsoever.49 Violation of this law results in the demolition of the structure, with the violator incurring the cost of demolition, fines of up to 10,000 Syrian pounds (SYP), and imprisonment for as long as six months.

In effect, rehabilitation works have been allowed in Yarmouk Camp since January 2021 and in Qabun since October 2022 by Decision no. 991.50 However, these permits were confined geographically to licensed buildings in less damaged neighborhoods. Rehabilitation remained forbidden in other parts of Qabun, Industrial Qabun, and Tadamun, either due to their inclusion in regulatory plans and/or their extensive destruction.

Furthermore, there have been reports of manipulation of technical damage by regime-affiliated businessmen and associates to prevent the return and rehabilitation of certain areas, with the intention of looting or purchasing properties at lower prices, as observed in Qabun and Industrial Qabun. In the former, conflicting decisions were also made by the different departments of the municipalities regarding the rehabilitation of factories and the return of their owners, as the area is supposedly under development.51 Eventually, owners were allowed to return in February 2021, but under the condition that they would be evicted again and their factories torn down whenever the regulatory plan was implemented, without compensation. Although the municipality announced that basic services like water and electricity would not be provided, 500 out of 750 factory owners applied for rehabilitation permits, demonstrating a clear desire of a majority of owners to return.

As shown in a previous article,52 Syrians are left alone to bear the cost of housing rehabilitation. Although a special compensation committee53 was established in September 2012 and provided 20 billion SYP until mid-2018,54 the beneficiary selection process was heavily politicized, favoring pro-regime communities while excluding former opposition areas under Syrian regime control since 2018. Compensation covers only 30-40% of the estimated value of damage. Moreover, funds provided by (I)NGOs are considerably limited and have been politicized and diverted by the Syrian regime, which forbids rehabilitation projects in informal areas and gives priority to the families of “martyrs” and wounded army members.

Besides lacking the financial capacity to rehabilitate their properties, Syrians encounter numerous other challenges, security issues chief among them. The Syrian regime fails to provide security for rehabilitated properties that might be looted again. Additionally, the supply of construction materials is monopolized by security and local military groups, resulting in unfair price hikes. Moreover, local contractors and businessmen often extort locals, many of whom cannot afford rehabilitation or rubble removal and fear confiscation or demolition of their properties, to sell or give up valuable construction materials at underrated prices. Under these circumstances, many displaced people who own property but cannot afford to rehabilitate it are forced to remain displaced and pay rents in other neighborhoods.

Urban Development and Regulatory Plans

While the Syrian regime was bombarding and bulldozing several neighborhoods in Damascus throughout the conflict, it rushed into preparing regulatory plans for the very same neighborhoods. Several decrees and laws related to urban development and investment were issued to facilitate land dispossession and the implementation of regulatory plans. Beside Law 9 of 1974, which authorizes local administrative units to appropriate up to half of privately owned land without compensation,55 there are four main recent laws that govern these processes:56

-

Law 15 of 2008, which permits the establishment of public administrative bodies with legal personality and financial and administrative independence. These bodies are responsible for regulating real estate development and encouraging investment, catering to both domestic and Arab investors.57

-

Decree 66 of 2012, which delineates two development zones in Damascus, situated in the southeastern zone of Mezzeh and the southern part of the southern ring.58

-

Law 23 of 2015, which pertains to zoning and urbanization implementation. It grants the state the authority to expropriate between 40% to 50% of properties within zoning areas for public benefit, without compensation.59

-

Law 10 of 2018, which allows the state to reclaim properties from individuals who fail to assert their ownership rights within a designated time frame, initially set at one month but later amended to one year, following the designation of an area for development.60

In pursuit of its vision, the Damascus Governorate Council announced in 2018 the preparation of regulatory plans for all informal areas around the city. However, it is worth paying attention to the council's statement that issuance of a plan does not necessarily imply immediate implementation, which “might take a long time.” Announced plans include: Barzeh, Qabun, Jober (planned for preparation between 2018 and 2019); Tadamun, Daf al-Shouk, Zaherah, Nahir Aisha, Zuhur (2019-2020); Qasyoun (Rukn al-Din, Muhajireen, Marabeh) (2020-2021); Dwail’a and Tabbaleh (2021-2022); Mezzeh 86 and Dummar informal settlements (2022-2023); and Madamiyet Elsham (2023-2024). In November 2023, the council announced that a private company was commissioned to design a master plan for a 59,000-hectare area of Damascus and its surroundings. However, the identity of the company, the details of the contract, and the fate of previously announced regulatory plans remain unknown.61

The five regulatory plans that have been officially announced and ratified so far within the administrative borders of Damascus are:

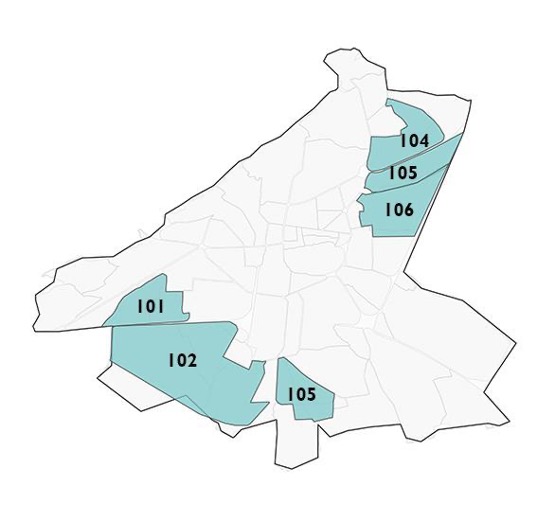

- Regulatory Plan no. 101 (Marota City): located in southeast Damascus and spanning over 214 hectares between Mezzeh and Kafr Souseh neighborhoods. The master plan was announced in December 2012. It encompasses 2,000 residential units within 186 residential towers (11-22 floors) and 33 plots designated for investments (up to 50 floors). Based on Law 66 of 2012, the municipality appropriated 50 plots for public facilities and governmental buildings and transferred their ownership to the Damascus Cham Holding Company.62

- Regulatory Plan no. 102 (Basilia City): located adjacent to the Southern Ring Road and extending into the neighborhoods of Qadam, Assali, and 30th Street. The master plan was officially ratified in July 2018. It extends over 900 hectares,63 encompassing 4,000 properties. According to Law 66 of 2012, objections were to be received within one month of ratification, potentially affecting more than 25,000 former households64 who lacked access and were unable to object due to security and administrative reasons.

- Regulatory Plan no. 104 (Damascus’s Northern Gate): announced in July 2019 and ratified by the Decree 237 of 2021.65 The area of the master plan is 215 hectares, including Industrial Qabun and parts of Harasta in Rural Damascus.66 It alters the land use of these areas from agricultural and industrial to residential and commercial.67 As part of the plan, all factories will be relocated to Adra Industrial City. Factory owners were given a one-year deadline to provide proof of ownership, which ended in October 2022. Specific committees will assess buildings within the development area, determine their number and status, estimate their value, and convert them into regulatory shares.

- Regulatory Plan no. 105: encompassing the residential Qabun neighborhood68 and Yarmouk Camp.69 The plan, which was proposed according to Law 23 of 2015, was approved in June 2020.70 It divided both neighborhoods into internal districts based on their level of destruction. Residents had one month to submit their objections to the master plan, resulting in more than 10,000 objections in Yarmouk Camp alone by August 2020.

- Regulatory Plan no. 106: announced in June 2022,71 this plan includes Jober, Qabun, Arbin, Zamalka, Masjid Aqsaab, and Ein Tarama. The master plan seeks to change the land use of such areas “from the area of (B) protection and (C) internal agricultural and (J) residential expansion to (I) areas under organization,” which allows for eight-floor residential buildings.72 Additionally, it proposes the Southern Ring Road as the new administrative boundary separating Damascus from Rural Damascus. Residents were also given only one month to submit their objections.

In January 2024, the head of Jaramana City Council announced the regulatory plan of Jaramana and invited residents to submit objections within 30 days.73 However, no details have yet been made public on the progress or processed objectives.

As of August 2024, it appeared that the implementation of most other regulatory plans, aside from Marota City and Basilia City, had not started. Despite serious doubts around their feasibility, between 2013 and 2015,74 thousands of residents were forcibly evicted to allow construction work on the Marota and Basilia projects to begin. Rent compensations offered to evacuees have been below the current market prices and were estimated drastically below the actual value of confiscated properties. Being transformed from homeowners to tenants, many evacuees were burdened with unnecessarily high rents and were ultimately forced to sell their designated shares in proposed projects to bridge the gap between costs and reimbursement, resulting in the effective permanent loss of home ownership. Making things worse, the completion of alternative housing projects has been delayed several times, with the most recent estimates suggesting new homes will not be ready before the end of 2025.75

According to Law 66 of 2012, at the time of eviction, only current occupants residing on state-owned land are eligible for alternative housing and two years of annual rent compensation (equivalent to 5% of the property value). However, evacuees are required to pay for allocated alternative housing units in 15-year installments (minus the estimated value of their original properties or the value of their rubble if they were illegally built), substantially undervaluing their properties. To avoid paying rent compensation and providing alternative housing, the regime pursued a policy of confining construction works to only depopulated areas (as in Basilia City),76 or of restricting return in areas where the implementation of plans was expected to start shortly, effectively aiming to obstruct IDPs from returning and becoming current occupants eligible for compensation and alternative housing benefits.

To fully capture how regulating new lands benefits the regime beyond the fulfillment of its political and social goals, we should recall recent laws that grant municipalities the right to appropriate without compensation up to 50% of regulated land for public services and investment purposes. Such appropriated lands in the capital are operated by Damascus Cham Holding, a public joint stock company established in 2012 to develop real estate areas in Damascus in partnership with private investors.77 In this sense, the government must be seen as an investor in the market rather than a mere regulator, which is embedded in a network of cronies, corrupt politicians, warlords, and businessmen. The interests of these actors sometimes conflict, disrupting the implementation of such plans.

However, the primary hindrances to the regime's progress in executing regulatory plans in other areas remain its limited financial capacity and the presence of cohesive communities in the areas that either have not witnessed large-scale destruction and displacement or where a sizable portion of the population has managed to return. For instance, the implementation of the regulatory plan was allegedly suspended in Yarmouk Camp due to pressure from Palestinian figures and political parties supported by returnees.78 Regime capacity is expected to further decrease in communities known to be pro-regime like Mezzeh 86 and Eish al-Werwer.

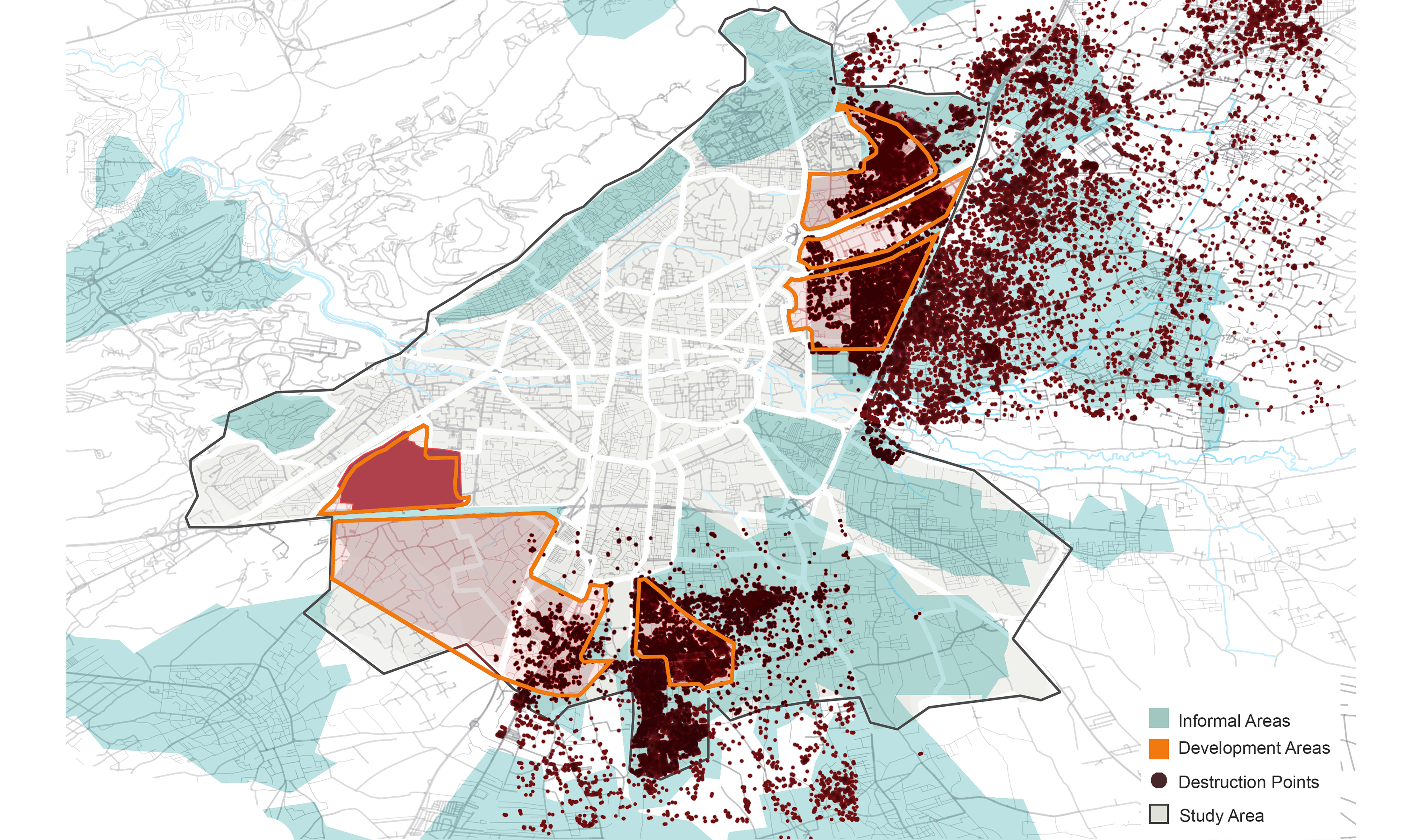

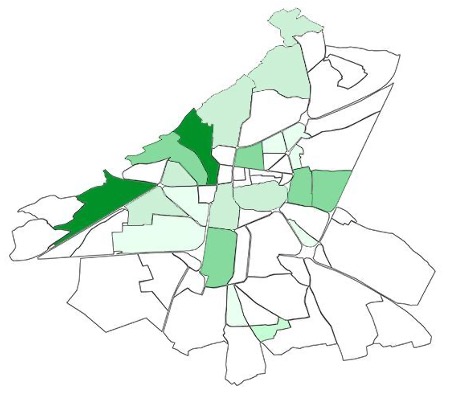

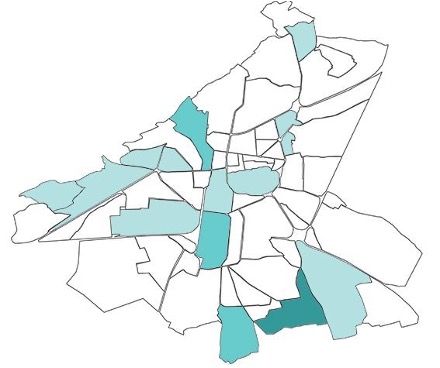

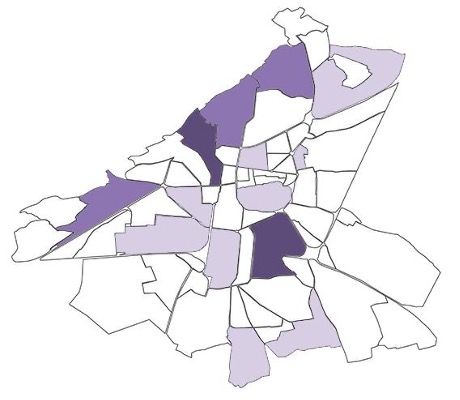

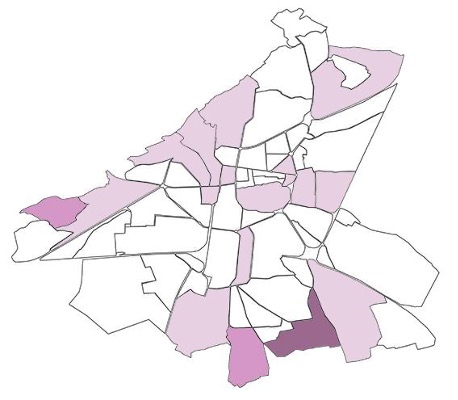

In summary, while the Syrian regime’s official rhetoric emphasizes the prioritization of return and recovery in conflict-affected areas, the current legal framework hinders progress. With little doubt, the restriction of recovery in neighborhoods that were formerly rebellious during the uprising is politically motivated. However, it also serves an economic agenda that involves the implementation of urban development plans in informal and working-class areas. These plans ultimately will alter the social fabric in these areas and enrich regime-linked businessmen and foreign allies. The correlation between informality, destruction, and reconstruction is clearly evident, as shown in Map 6.

Rehabilitation and Early Recovery Policies in Damascus

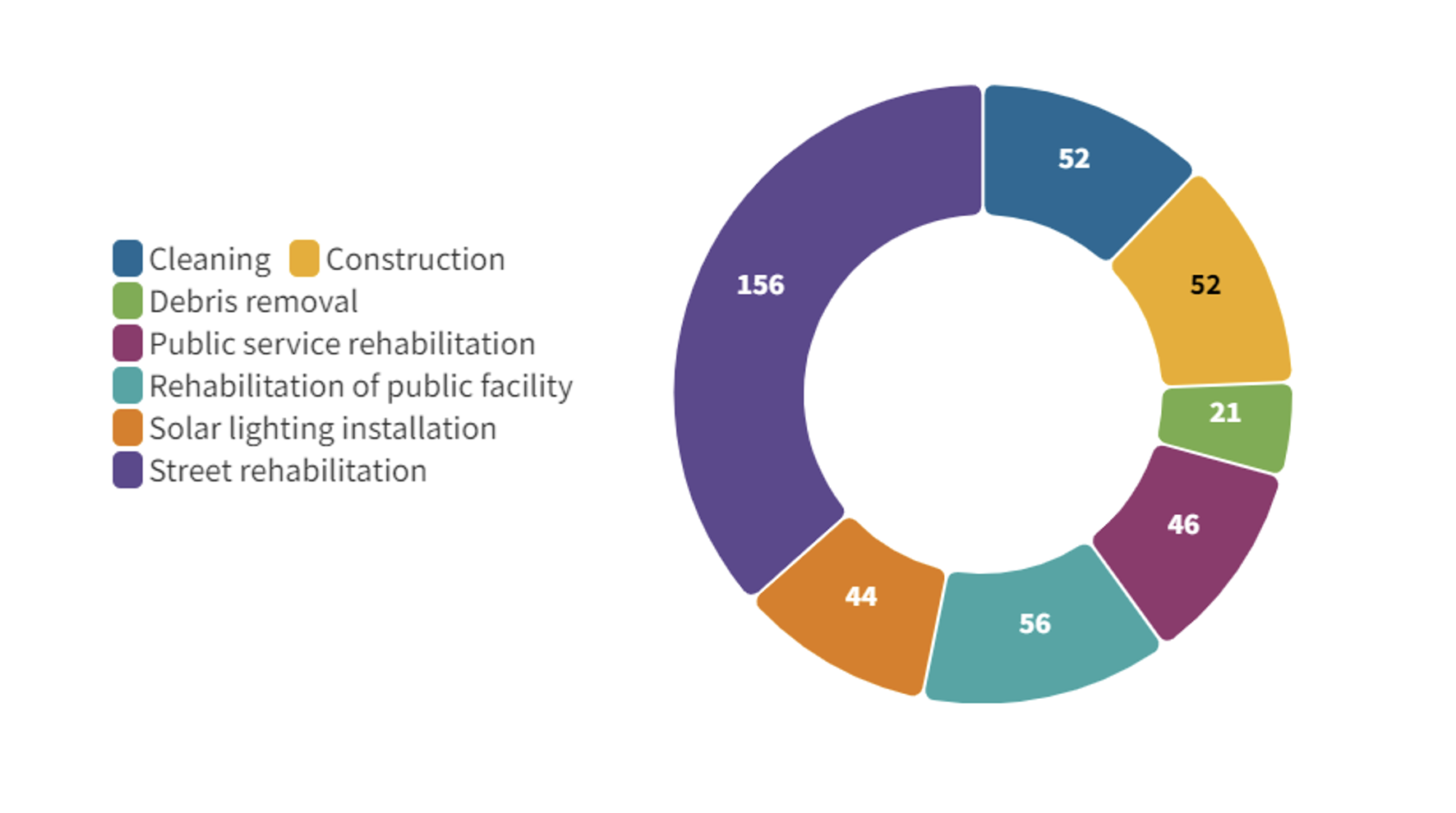

This section presents an analysis of the rehabilitation and early recovery activities carried out by the Damascus Governorate Council (DGC) and Rural Damascus Governorate Council (RDGC) in the capital and southern suburbs from January 2021 to August 2023. The data was sourced from the council's media Facebook pages.79 A total of 446 activities were mapped and broadly categorized under four main groups: street rehabilitation, debris removal, streetlight installation and repair, and rehabilitation of public services and facilities. As demonstrated in Figure 3, street rehabilitation emerges as the top priority for both municipalities, followed by rehabilitation of public facilities, cleaning campaigns, and small-scale construction activities like retaining walls and staircases. Additionally, significant attention was given to construction activities for the Marota City and Basilia City development projects.

It is important to recognize that while this analysis does not offer comprehensive overviews of the early recovery efforts around the city, it aims to get some sense of the Syrian regime’s geographic and sectoral priorities in terms of early recovery and rehabilitation. By doing so, it attempts to identify trends and patterns related to the regime's reconstruction policies and visions. Activities included in this section are limited to those carried out directly by the DGC and the RDGC or those implemented by NGOs or UN agencies in collaboration with the councils and advertised by the councils as such.

It is worth noting that the DGC prioritized the demolition of unlicensed construction and the imposition of penalties on officers who covered up these violations or failed to report them.80 Such demolition decisions were also applied in informal settlements and conflict-affected areas, including households attempting to rehabilitate their conflict-affected buildings.

Street Rehabilitation

Upon initial examination, street rehabilitation activities were concentrated in regulated areas and those least impacted by the conflict such as Mezzeh, Salhiyeh, Muhajireen, Mezzeh 86, Adwi, and Midan. The 156 identified activities primarily consisted of small-scale street asphalt repairs, solutions for potholes and driveway cracks, and the installation of asphalt pavement. All these activities were undertaken by the council’s Directorate of Maintenance and Services, with the primary contractor being the Military Construction Establishment,81 a state-run construction company managed by the Ministry of Defense that has been sanctioned by the United States and the European Union. In southern Damascus, some collaboration with civil society organizations and the private sector was observed. Furthermore, in Sayyeda Zeinab, a stronghold for Iranian militia groups in southern Damascus, repair projects for the main roads in the neighborhood were implemented by Jihad al-Bina, a development foundation run by Hezbollah in Lebanon.82

However, despite the persisting need for street rehabilitation in most neighborhoods, the scale of work remains notably limited and of minimal quality. Potholes present a significant challenge in many Damascus streets,83 particularly in informal areas where pavement is less common and the use of more primitive materials prevails. According to the DGC, 3 billion SYP (approx. $350,000) was allocated for street rehabilitation in 2023, distributed across four contracts. Despite several promises made by the DGC in recent years, the reality of Damascus’s streets has not seemed to be improved. For example, the DGC declared 2019 “the year of road paving,”84 but the campaign primarily focused on Mezzeh 86, an informal neighborhood with a majority of residents known to be pro-regime. A similar promise was made in April 2023,85 but there was no noticeable increase in activities between May and July of that year, as seen in Figure 4.

There is a clear bias in the geographical distribution of activities against conflict-affected neighborhoods, even in areas where rubble has been removed by the DGC. Indeed, street rehabilitation is profoundly important for the recovery of affected neighborhoods for several reasons, including the reconnection of isolated areas with the city’s economic and service nodes such as hospitals and schools and the restoration of transportation services to make the neighborhoods accessible by returnees. Additionally, repairing main streets can streamline the process of debris removal, solid waste collection, and basic infrastructure repair by enabling heavier equipment and vehicles to access smaller and less connected neighborhoods.

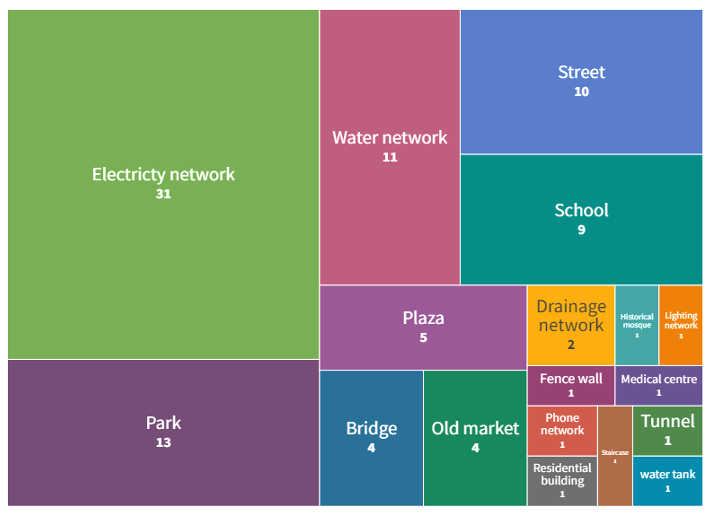

Rehabilitation of Public Facilities

The primary focus of repair activities revolves around the rehabilitation of facility buildings and improvement of service infrastructure. Key sectors targeted for repair include the electricity network, followed by installation or repairing of road infrastructure, schools, parks, and water networks. Yalda emerges as the area with the most extensive rehabilitation efforts, followed by Salhiyeh, al-Hajar al-Aswad, Midan, Old Damascus, and Sayyeda Zeinab.

The rehabilitation of the electricity network primarily involved the installation of power transformers or increasing existing capacity, although this was less common in conflict-affected areas. There were slightly more activities in al-Hajar al-Aswad and Yalda, thanks to the role of civil society initiatives.

Enhancing and beautifying parks emerged as a secondary priority for the DGC. However, these activities were concentrated in high-class neighborhoods such as Maliki, Abou Rummaneh, Mezzeh, and Western Villat. School rehabilitation projects primarily took place in Yalda, led by NGO-funded initiatives.

Apparently, rehabilitation of water networks and drainage systems received less priority, especially in conflict-affected areas despite the high level of their destruction and surging demand for these services. Similar to street rehabilitation, a discrepancy in the allocation of resources underscores biases both in terms of sectors and geographical distribution by the regime, especially in informal and conflict-affected areas. This could have implications for discouraging the return of residents to areas lacking the necessary infrastructure and basic services.

While civil society initiatives have filled some gaps in service provision and infrastructure rehabilitation in some parts of southern Damascus, it appears that there is limited space for NGOs to operate in a similar capacity within Damascus itself.

Street Light Installation

During the study period, 44 activities were carried out involving the installation of street lighting or maintenance of existing lighting units. Many of these projects were promoted as a part of the DGC’s strategy to transition towards alternative energy sources, which remains a persisting priority due to the constant inadequacy of fuel and electricity in regime-controlled areas. The DGC’s Local Development Committee and the Electricity Directorate are the main entities responsible for these activities, a considerable part of which were funded by the private sector or NGOs. According to the DGC, in 2022, they installed 1,040 solar lighting units around the city, with 190 units funded by local initiatives and the private sector.86 The main areas targeted by this campaign included Mezzeh 86, Qadam, Sheikh Saed, Barzeh, Misat, Tishrine, Midan, and Moujtahed.

Geographically, based on our data, Rukn al-Din, Salhiyeh, Shaghour, and Mezzeh are the main neighborhoods benefiting from these projects, while conflict-affected areas have been largely excluded.

Indeed, lighting plays a crucial role in facilitating the return of residents to conflict-affected neighborhoods. It significantly improves overall security and a sense of safety, especially in secondary streets. Given the complete destruction of electricity in these areas, along with ongoing incidents of looting, solar lighting presents a viable solution for encouraging return and ensuring the safety of returnees and their properties.

Debris Removal

Debris removal ranked as the lowest priority for the DGC since 2021, with only 21 recorded activities related to rubble removal. Less than half of these activities were focused on removing debris caused by the conflict in neighborhoods such as al-Hajar al-Aswad, Qabun, and Tadamun. The remaining activities involved clearing rubble from collapsed buildings or accumulated solid waste in other neighborhoods.

As discussed in the previous section, it is evident that the Syrian regime places a low priority on debris removal, despite publicized campaigns promoting increased removal efforts to facilitate the return of residents. In reality, the burden of this task has largely been placed on the shoulders of ordinary people seeking to return to their properties.

Primary Findings

After reviewing the activities of rehabilitation and early recovery carried out by the DGC and RDGC in both Damascus and Rural Damascus, it becomes clear that the recovery of conflict-affected neighborhoods and the return of displaced residents are not among the priorities of the Syrian regime. Several significant patterns and biases can be observed:

-

Uneven Geographical Distribution: Projects are unevenly distributed in favor of wealthier and non-damaged neighborhoods, leaving informal and damaged communities with less attention. The exceptions are neighborhoods like Mezzeh 86, which is known to be pro-regime, and certain areas in southern Damascus where civil society organizations were given space to operate.

-

Sectoral Bias: There is also a sectoral bias in the distribution of projects. Resources are dedicated to improving street fixtures and public parks in high-class neighborhoods at the expense of investment in critical needs in informal and damaged neighborhoods, such as debris removal and the rehabilitation of drainage and water networks.

-

Limited Quantity of Projects: Given the size of Damascus, the quantity of projects implemented is very limited and inadequate. For example, despite previous announcements that major campaigns were undertaken to rehabilitate streets in Mezzeh 86, an obvious high demand for that service has persisted. Economic deterioration in the country and a declining state budget contribute to this inadequacy, as does corruption within public institutions. Public opinion on social media platforms reflects dissatisfaction with the inadequacy of these projects to meet local needs.

-

Civil Society's Role: Civil society organizations have demonstrated their potential to fill gaps left by the councils, as seen in southern Damascus. However, they require space and a suitable operational environment. In areas where the Syrian regime is determined to implement its regulatory plans, like Qabun and Jober, civil initiatives have remained totally restricted.

In sum, while the Syrian regime is sponsoring luxurious urban development projects such as Marota City and Basilia City and large touristic investment projects such as the Nirvana Hotel in the historic Hijaz Quarter, minimal efforts appear to have been made in areas with greater needs, including informal and conflict-affected neighborhoods. This uneven distribution of resources reveals that the Syrian regime remains committed to its pre-conflict economic and political policies of prioritizing neo-liberal urban development over the welfare of poor and, currently, damaged neighborhoods. Despite its official rhetoric, the Syrian regime is not taking practical steps to legally or economically facilitate the return of IDPs and the rehabilitation of damaged properties but is instead going ahead with its pre-conflict urban development projects.

Case Studies

This section will investigate two case studies representing different approaches to post-conflict arrangements in Damascus. The case of Qabun and Jober demonstrates a completely restricted recovery for areas slated for urban development, while the case of southern Damascus shows restrictive and selective return and rehabilitation. In Yarmouk Camp, the role of the local society in improving return conditions and pushing back against restrictions imposed by the regime will be discussed.

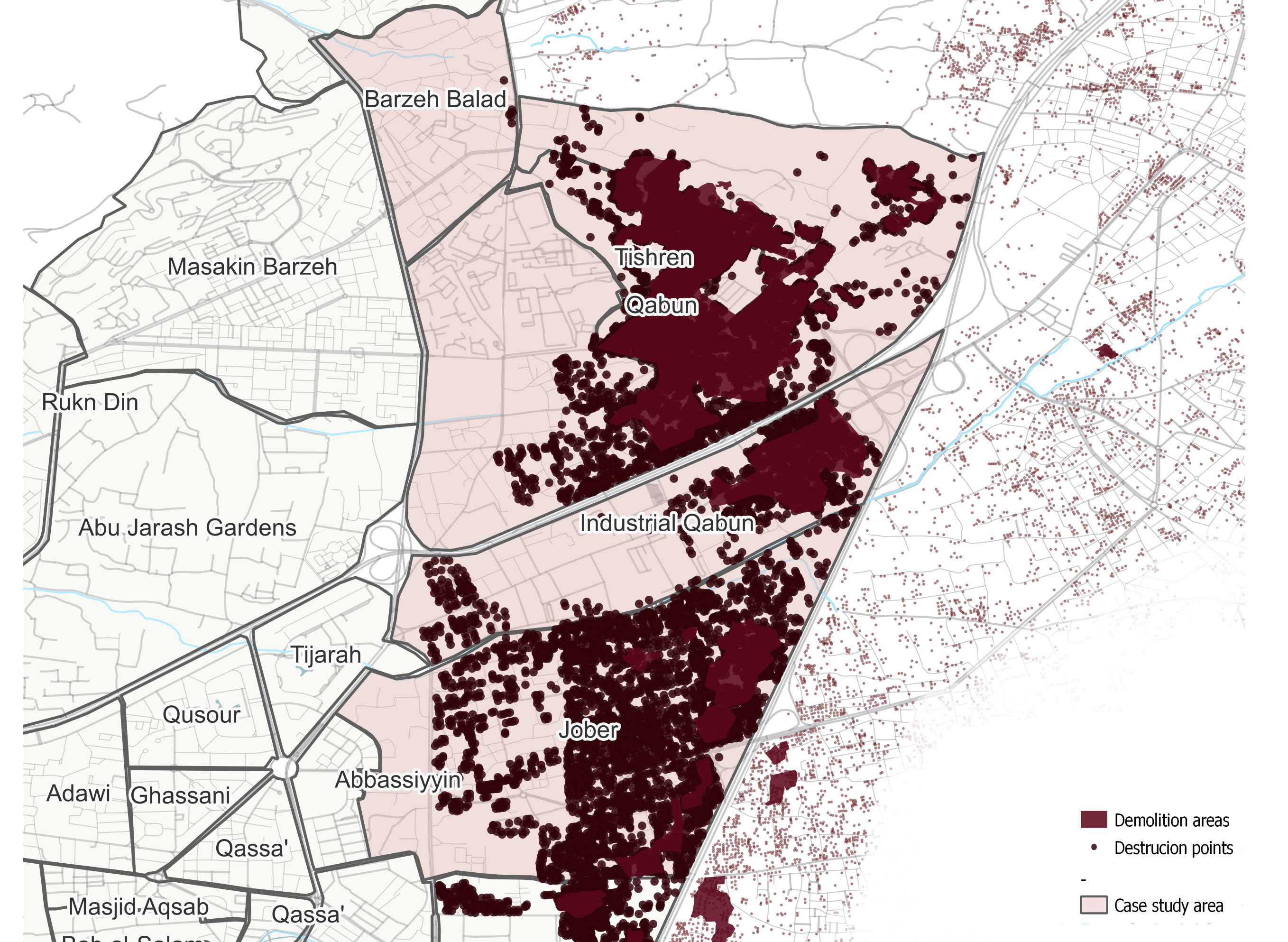

Qabun and Jober: No Return, No Reconstruction

The broader Qabun district is situated at the northeastern edge of Damascus, geographically connected with Eastern Ghouta. It comprises diverse communities, including Qabun al-Balad, Industrial Qabun, and Tishrine (an informal settlement), and is bordered by Barzeh Balad and Eish al-Werwer (a majority Alawite informal area) to the north and Jober to the south. As a result, the district houses a mix of original Damascene inhabitants,87 industrialist families, and low-income migrants and workers. Following its annexation by Damascus Governorate in the 1960s, the district experienced a rapid surge in construction activities, primarily of an informal nature,88 encroaching upon agricultural lands. Over time, the Syrian regime has proposed various redevelopment plans for the area,89 including the demolition of informal settlements and development by private investors. Consequently, significant areas of agricultural land were confiscated, and numerous residential buildings were demolished to make way for highways and government structures.

Between 2011 and 2014, Qabun and Jober emerged as hubs for anti-regime protests and military activities of the FSA. During this period, the Syrian regime strategically prioritized isolating these areas from another major opposition stronghold in Eastern Ghouta. This strategy involved imposing sieges, subjecting the two neighborhoods to bombardment, displacing a portion of their population, and extensively demolishing residential buildings to create a buffer zone. Following a truce agreement reached in Barzeh in 2014, the area experienced a relative period of calm before the regime launched its last military campaigns between February 2017 and March 2018 and subsequently gained control of Qabun and Jober.90 These offensives resulted in additional destruction in Qabun and Tishrine and forced evacuation of the remaining residents. By May 2017, approximately 2,300 people had been displaced from Qabun and 1,200 from Barzeh and Tishrine.91 Qabun and Jober were effectively depopulated with fewer than 100 individuals remaining in the Qabun area by June 2017 and 200 in Jober — communities whose populations were estimated at 89,974 and 83,245 respectively in 2004. Barzeh retained a relatively larger population, with 25,000 remaining, according to OCHA.92 However, this still marked a significant drop from its pre-conflict population, which was recorded as 107,596 in the 2004 census.93

The area fell under the control of the Republican Guards and Air Force Intelligence, resulting in widespread looting and the sale of stolen goods in nearby markets in Jaramana, Mezzeh 86, and Soumariyyeh.94 A few months after the regime takeover, a systematic demolition campaign ensued, employing bulldozers and explosives to reduce vast portions of the neighborhood to rubble.95 These demolitions were rationalized under the pretexts of "demining activities" or "structural safety measures." Demolition campaigns continued until 2022, resulting in the leveling of most remaining structures,96 including residential buildings, schools, mosques, and public buildings, transforming these once-thriving residential and commercial districts into desolate wastelands. As of February 2018, UNOSAT estimated the extent of destruction in Jober at 93%,97 while destruction in Qabun and Industrial Qabun was assessed by the DGC as at least 80%.98

The extensive level of destruction and restrictions on return can arguably be attributed more to the reconstruction or the so-called “regulatory statuses of these areas,” rather than their military history during the conflict, especially considering that a substantial amount of the destruction took place following the regime’s military takeover. Nevertheless, due to the regime's lack of adequate resources and inability to secure external funds to implement the announced plans, namely 105 and 106, it eventually allowed a limited return to Qabun in October 2022,99 with the return to Jober remaining so far prohibited.100 However, the harsh conditions attached to the return decision, such as the requirements to rehabilitate properties within six months of receiving the permit, sign a pledge to forfeit any right to compensation when the regulatory plan is implemented, and obtain a security clearance, have rendered the return impractical for the majority of IDPs and refugees. Meanwhile, looting activities continued in both Qabun and Jober.101 These activities are sponsored by the Fourth Division and the NDF in cooperation with Mohammad Hamsho, a regime-linked businessman who allegedly monopolizes the business of iron scrapping and recycling in Damascus and Rural Damascus.

According to A. K., a resident of Qabun:102

Only a few people have managed to return to Qabun, while the majority were barred under the pretext of reconstruction or extensive damage. Everyone I know wishes to return to their homes. They do not care about what might happen afterwards or what form the reconstruction might take. They are simply exhausted and unwilling to pay rent elsewhere when they own houses they are prohibited from returning to.

In addition to the legal and security challenges, the practicality of return has been complicated by the absence of basic services and the lack of financial support for rehabilitation.103 More crucially, fear of the implementation of regulatory plans and the potential demolition of their properties has been a major deterrence for many to return. The regime continues to deny people permission to return for two reasons. First, the government seeks to avoid the cost of providing alternative housing when implementing the regulatory plans, as the law restricts access to such compensation only to current occupants,104 a condition that does not apply to displaced individuals as long as they remain displaced. Second, the government seeks to avoid confrontations with residents when the implementation of regulatory plans becomes feasible and eviction becomes necessary. Under this circumstance, IDPs are left with a dilemma: to continue to pay high rents in their places of displacement, or to seek return and invest a substantial amount of capital, which the majority lack, to repair their properties with the potential of losing them again in the near future.

The proposed regulatory plan not only disregards the participation of locals and the preservation of the pre-conflict social, urban, and economic fabric, but also actively seeks to strip people of their properties without compensation. Although residents have been granted 30 days to file objections, the fact that the majority of the residents are displaced, wanted for security reasons, or afraid to object renders this utterly pointless. Ultimately, despite the regime having no resources to implement the regulatory plan in the near future, it continues to deny permission to return, probably with an eye to preventing complications should implementation eventually become feasible.

Southern Damascus: Local Resistance to a Denied Recovery

Southern Damascus refers to an area encompassing several neighborhoods and towns that lay along the southern periphery of the city extending into Rural Damascus Governorate. Among the major communities in southern Damascus are Yarmouk Camp, al-Hajar al-Aswad, Tadamun, Yalda, Sbeineh, and Babella. Aside from their geographical proximity, these communities share several characteristics. First, they have a mixed population composed of Palestinian refugees, Syrians displaced from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights in 1967, and Syrians who migrated from other governorates seeking cheap accommodation. Second, they exhibit a high population density relative to their small area. The population of Yarmouk Camp was estimated at 600,000, including around 160,000 Palestinians, as of 2011,105 while there were 84,948 residents in al-Hajar al-Aswad and 86,793 in Tadamun, as of 2004’s census.106 Third, they possess an informal and haphazard urban environment, which is associated with a low level of service provision and infrastructure. Fourth, prior to the conflict, their governance has been subject to a complex overlap between the Damascus Governorate Council, the Rural Damascus Governorate Council, the Quneitra Governorate Council (responsible for the affairs of IDPs from Golan), the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), and various Palestinian political and military factions.

During the conflict, southern Damascus was subject to control by various military actors and experienced numerous periods of intense destruction and displacement. Between 2012 and 2013, the FSA took control of the entirety of Yarmouk Camp and al-Hajar al-Aswad, as well as the southern portion of Tadamun. In response, ousted regime forces imposed a multi-year siege upon the remaining population, which was often accompanied by intensive bombardment that devastated a multitude of residential buildings and infrastructure. In 2014, jihadist groups, including ISIS and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), gained control of a significant portion of Yarmouk Camp and al-Hajar al-Aswad, forcing FSA factions to retreat towards Qadam, Yalda, and Babella.107 This situation persisted until the Syrian regime launched its largest and last offensive between March and May 2018, resulting in widespread destruction and the displacement of the remaining population and fighters to northern Syria. Additionally, ISIS members were relocated to the Syrian desert after reaching an agreement with the Syrian regime and Hezbollah.108

Upon the regime's takeover of southern Damascus in 2018, the area came under the control of the Fourth Division, which immediately imposed restrictions on the movement of people to and from the area. Displaced individuals were also prohibited from transferring furniture to their new accommodations without securing a special permit, which frequently entailed paying bribes at checkpoints. The remaining furniture as well as construction and cladding materials were systematically looted in campaigns orchestrated by local gangs in collaboration with security forces and local militia groups. The first round of looting targeted furniture and electronic appliances left behind by their owners. Looted goods were sold in specialized markets in nearby villages and neighborhoods, including Soumariyyeh, Eish al-Werwer, and Tadamun. The second phase of looting focused on copper cables, aluminum and wooden frames, tiles, and other valuables. Finally, iron rods were pilfered from concrete slabs and structural beams, resulting in the partial or complete collapse of many buildings. Muhammad Hamsho,109 a regime-linked crony, is believed to be the main figure in the scraping and iron recycling business, in cooperation with looting gangs and the Fourth Division.

The Camp Local Committee, the local governing body in Yarmouk Camp before 2011, was dissolved in October 2018, bringing the camp administration under the administration of the DGC.110 Local committees were later dispatched by the DGC to inspect buildings in each neighborhood, categorizing them into three groups: 1) safe for habitation, 2) requiring rehabilitation, or 3) earmarked for demolition. However, several incidents cast doubts on the accuracy of such estimations.

In Tadamun, the first inspection committee created by the DGC in July 2018 estimated only 690 buildings suitable for temporary return in the neighborhood, but this estimation was modified to 2,500 in 2020 under pressure applied by residents with support from the NDF.111 Furthermore, interviewees told the author that the classification of a building’s structural status can be altered by committee members from demolition to renovation in exchange for bribes ranging from 1 to 10 million SYP ($70 to $700). Some families were willing to pay this amount and risk living in a structurally unsound building to avoid paying high rents somewhere else. Between January and February 2024, four buildings collapsed in Damascus during periods of heavy rain, resulting in the death of two people.112

Security forces and local militia groups marked houses belonging to families killed or displaced to northern Syria during the conflict, making them prime targets for looting or fraudulent property transfers. Moreover, several reports suggest that even structurally sound buildings were arbitrarily demolished by rubble removal contractors and looting gangs to extract their iron rods and other materials, causing further damage to already devastated areas.113 For example, as of March 2022, more than 300 buildings had been completely demolished by the DGC in Tadamun around the Salman Farsi Mosque and Tarboush Quarter.114 Rubble was moved to the Tabab neighborhood, an informal area occupied previously by public servants that was demolished in 2013 by the Republican Guards and the NDF.

After major looting activities were completed, security authority was transferred from the Fourth Division to different branches of Military Security such as Branch 227 (or the District Branch), which became responsible for al-Hajar al-Aswad, Yarmouk Camp, Qadam, and Tadamun, and Branch 235 (or Palestine Branch) governing Yalda, Babella, and Beit Sahem.

Displaced residents of southern Damascus had to wait two years until a conditional return was finally allowed to Yarmouk Camp in October 2020 and al-Hajar al-Aswad in September 2021. Return applications for Yarmouk Camp were submitted at the Palestine Branch, and applicants were required to attend several sessions of interrogation. Those who lived in these neighborhoods when they were controlled by opposition forces were faced with possible imprisonment for periods of three months to one year, charges of “aiding terrorist activities,” and/or confiscation of their property,115 while people who left the area before the control of the opposition were required to provide rental contracts showing their previous location of residence.

Despite the inadequate services and infrastructure, many residents expressed their willingness to go home, as manifested by 1,200 applications submitted within three months for return to Yarmouk Camp, of which only 500 were approved by the regime.116 The main motivation of those seeking to return to south Damascus seems to be to avoid paying high rents for temporary lodging in areas to which they had been displaced. However, the inability to obtain security clearance and the lack of financial capacity to rehabilitate damaged properties present significant barriers to return. It is worth noting that the majority of returnees in southern Damascus are among those who were displaced to neighborhoods within Damascus or other regime-controlled areas in southern Syria, with fewer cases of return from Jordan and Lebanon. Return from opposition-controlled areas remains almost non-existent. In al-Hajar al-Aswad, the returnees are mainly coming from Quneitra Governorate (to which they originally had been displaced by the Israeli occupation of the Golan Heights in 1967).

Based on a field visit in southern Damascus, return was mainly allowed to a few quarters adjacent to major roads such as Palestine Street, Loubia Street, and Schools Street, particularly around the Bashir Mosque, the Old Vegetable Market, and Palestine Park, while return remains mainly prohibited in areas adjacent to 30th Street, 15th Street, and Jazeera Street. In Tadamun, return has been allowed in quarters between Ibn Battuta Street and Stars Cinema.

In al-Hajar al-Aswad, the main districts where return was allowed are Wehdeh and Istiqlal117 and a few quarters adjacent to Ibrahim Khalil Mosque. The districts of Tishrine and Thawra have seen a lesser percentage of return due to the high level of destruction. Similarly, return in Jazeera, Aa’laaf,118 and Jolan119 continues to be limited and these neighborhoods remain highly depopulated, posing a security challenge for those families that do attempt to come back.

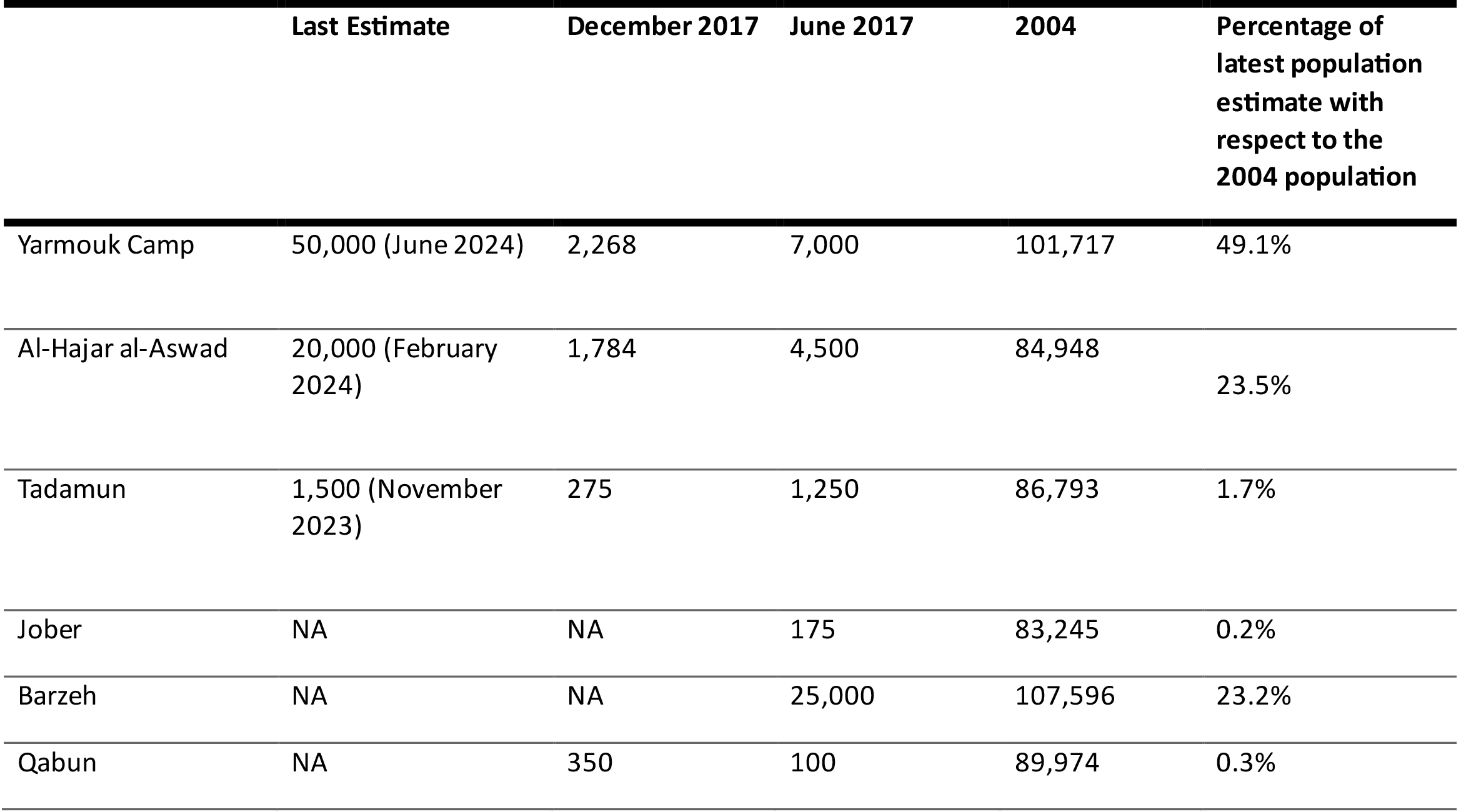

As shown in Table 1, the population of conflict-affected neighborhoods, which has significantly decreased throughout the conflict, failed to recover after more than six years of the regime's control.

As of November 2023, only 1,500 individuals were estimated to have returned to Tadamun,120 1,500 families in al-Hajar al-Aswad, and 20,000 individuals in Yarmouk Camp.121 However, by June 2024, these numbers had increased to 50,000 in Yarmouk Camp, according to the Action Group for Palestinians of Syria,122 and 20,000 in al-Hajar al-Aswad, according to al-Hajar al-Aswad Municipal Council.123 Although only a fraction of the original inhabitants have returned as of mid-2024, these numbers represent a major increase compared to the population remaining following the displacement agreements in 2017,124 as shown in Table 1.

The DGC’s debris removal activities in southern Damascus were confined to main streets and only in sectors that were marked as suitable for residence. Locals often were invited to participate in campaigns to remove and transport debris from main roads, but removing rubble from side streets and within the neighborhoods has been ultimately the responsibility of the residents themselves. It must be noted that removing the debris is only allowed in specific periods set by the DGC. During early years of the regime's control, a number of local initiatives were led by local councils or civic actors to remove debris or repair public facilities, (often supported by local Palestinian organizations in Yarmouk Camp), with many cases of people participating directly in removing rubble from their streets. However, the incapacity of local governance structures, the lack of an adequate workforce, and diminished hope for return and restoration of basic services have weakened enthusiasm for such activities. Instead, local contractors became responsible for debris removal in most neighborhoods in southern Damascus, operating alongside other contractors responsible for property rehabilitation, which are also able to supply construction materials in cooperation with local checkpoints.

According to A. R., a resident of Yarmouk Camp:125

Those who return feel as though they are living amidst rubble. People understand that the regime lacks the funds to reconstruct their neighborhoods, and decisions on return and rehabilitation are solely made by security branches. The regime merely adopts the rhetoric of reconstruction to attract international funds and to extract some cash from remittances sent by Syrians abroad to assist their relatives inside the country. Ultimately, people are not just paying to reconstruct their properties out of their own pockets, they also have to pay bribes at checkpoints to inspect their properties or to retrieve their furniture from the neighborhood. Despite all this, people still seek to return to their homes to avoid paying rent elsewhere.

Basic services such as water, electricity, and public transportation are absent from most neighborhoods. Some locals living adjacent to the less affected areas managed to connect to the electricity network through local cables or established collective generators, and some households dug local wells to secure a water supply. In Yarmouk Camp, a number of pharmacies and grocery and building material shops reopened on main streets after lights were installed, and a few schools were rehabilitated by the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). However, local Facebook groups often post pictures of looting incidents targeting recently rehabilitated facilities such as drainage networks, solar light posts, electricity cables,126 and houses127 that were marked as suitable for living. For example, all iron manhole covers installed in southern Damascus in recent years have been stolen,128 raising a high security risk for locals who often fall in the holes at night due to the lack of adequate lighting.

According to M. J., a former resident of al-Hajar al-Aswad:129

When the regulatory plans were announced, people were optimistic about the potential reconstruction of their neighborhoods and the prospect of their land values increasing. However, the implementation of regulatory plans in other areas, such as Basilia City, and the reality of reconstruction and rehabilitation practices in their own areas, led to a complete loss of hope among the majority of residents. Even those who had planned to return to Southern Damascus a few years ago have now changed their minds, knowing that they would be returning to areas with building violations [informal settlements]. Some returnees are already looking for ways to leave again. The primary strategy for many residents now is to sell their properties at any price to avoid losing them completely in the near future. Essentially, people are aware that the regime has future plans for these areas and that it will raze them to the ground sooner or later.